Cwik Sisters in Hammock in the Polish countryside outside of Vilna

Top Row: Children of the oldest sister, Fania; Leah Pasynski and David Belkind

Middle Row: Dweira and Mera

Bottom Row: Ela (later Ella Lidsky), Chana and Mariana

The Lidsky-Weinstein Family

The Weinstein family immigrated from Vilna to New York in the late 1800’s. Mrs. Weinstein gave birth to a daughter, Betsy, in 1893. For some reason, the Weinsteins decided to return to Vilna in 1896, when little Betsy was only three. Possibly, it was because news arrived that the parents back in Russia had gotten sick and needed one of their children to come back and take care of them. At that time, Vilna was part of Czarist Russia. The Weinsteins had three children, two girls and one boy. They owned a cardboard box factory and manufactured shoe boxes. Betsy’s son Alexander would later tell stories of playing in the factory and jumping into piles of boxes.

Top Row, left to right: Betsy Lidsky (nee Weinstein) and her sister Middle Row: Yascha (later moved to Russia), Mr. and Mrs. Weinstein

A good student, Betsy Lidsky studied pediatrics at the Stephan Batory University in Vilna. She was one of the only female doctors at that time. She married a surgeon, Abraham David Lidsky. Abraham David had been drafted into the Czar’s army during World War I. He was taken prisoner, but according to Alexander Lidsky, it was a relatively benign captivity. He had a French and an English prison mate. Abraham David learned English from the Englishman. Later in life, he would read Penguin novels in English. Dr. Betsy Weinstein and Dr. Abraham David Lidsky married. On November 18, 1920, Betsy gave birth to identical twin boys: Tolka and Alexander.

Left to Right: Alexander, Betsy, Abraham David Alexander and Tolka Lidsky

At the age of 15, Tolka developed a palsy which paralyzed the left side of his mouth. This made it easier to distinguish the two brothers. The Lidsky’s were Yiddishists: members of a secular Jewish movement believing that their home was Poland, but that they had their own culture expressed in the language of Yiddish. The parents spoke Polish in the hospital, but Yiddish at home. The boys were sent to Yiddish-speaking school until the 4th grade. Later they attended Epstein high school. Although they were twins, each one had a separate circle of friends.

Tolka was more gregarious and outgoing; Alexander had a smaller circle. Alexander remembers this as an idyllic time. In the summer, the family spent time at their nearby datcha in Velokumpia, on the Vilya river near Vilna. Abraham David taught his children to swim by trial of fire: taking one in each arm and flinging them into the Vilya. In winter, the father would take the twins skating and they would drink hot cocoa. On one occasion, Abraham David spilled hot cocoa on the table and said in a loud voice “Alexander, so clumsy, you spilled the cocoa!”. Alexander kept quiet and was later rewarded with a second cup of cocoa, since he had taken the fall for his father. In 1938, Drs. Betsy and Abraham David Lidsky sent their twin sons to Montpelier, France for pre-medical training, but the twins were not interested in medicine. They spent most of their time drinking, gambling and chasing women.

Starting in 1939, the Nazis occupied one part of Poland, and the Soviets occupied the other part, which included Vilna. The Soviets partitioned the Lidsky’s apartment to fit more people, but the Lidskys did not suffer from violence. The university was now run by the Soviets. Alexander went back to school, but again he showed less interest in studying than in enjoying life. In June 1941, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact collapsed as the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, including Vilna. The Jews of Vilna did not realize it at that moment, but this was the beginning of their genocide and annihilation. All Jews were ordered to leave their homes and relocate to the medieval Jewish ghetto, bringing only what they could carry. The Lidskys brought picnic baskets of food, but no warm clothing. It was early summer and they assumed that this would be a temporary hardship, lasting two weeks. They were mistaken.

Conditions in the ghetto were crowded. A German document accompanying this website lists Betsy Lidsky as one of 35 people inhabiting one apartment. Dr. Abraham David Lidsky and Dr. Pesia (Betsy) Lidsky worked in the ghetto hospital. The two sons, Alinke and Tolka, washed floors there. It was difficult for doctors to practice medicine properly because they lacked basic supplies. The Nazis issued a document, called a “shine”, to those who worked. Owners of shines would not be taken away in “actions” and sent to camps. If a man had a shine, he was allowed to write his wife’s name on it, and she would be safe from deportation as well. Even though the twins were single, at various times they “married” women in the ghetto to protect them. In one instance, the 21 year old Alexander “married” a 70 year old woman. Years after the war, in New York parties attended by survivors of the Vilna ghetto, Alexander Lidsky would introduce his son to a woman and say with a smile, “she was my wife.” The officers of the Wermacht (German army) and the officers of the SS were sometimes at cross purposes. The Wermacht was practical, needed able bodied men and women as labor for the war effort, and sought to use Jewish slave labor. It would not be in the Wermacht’s interest to have an outbreak of cholera decimate the labor force, and that is why shines were issued to hospital workers. The SS was ideological and sought to eliminate the Jewish race as part of Hiter’s Final Solution. Eventually, a shine was not a guarantee.

Dr. Abraham Lidsky was taken in an action in the middle of the night in 1943. He was taken to a concentration camp in Vivary (Estonia) and eventually to Fischausen where he was murdered by the Nazis. The book, The Martyrdom of Jewish Physicians in Poland, contains a print of the handwritten letter which Dr. Abraham Lidsky wrote to his wife, on September 5, 1943. The letter was delivered to Dr. Betsy Lidsky at the Jewish Hospital in Vilna by a Jewish policeman who accompanied the transportation train:

Dear Pesia,

We are in the cars and will travel about three days. If you have sent things for me, I was told that it will be given to me when we arrive at the place. We were given bread, soup and cinalco (local soda water).

Be quite and believe in destiny. If fate has separated us and if our misfortune is that we will not meet, I hope we will – you and the children – find each one his own way. Be quiet. I kiss you all.

So it is our fate. Perhaps it is predestined for each of us or for some of us to have a quiet future.

I kiss you.

Abraham

By the end of September, the liquidation of the Vilna ghetto was complete. A small number of Jews, about one or two thousand, were relocated to local slave labor camps. An even smaller number, who were members of the FPO (Jewish Resistance) escaped to the forest where they joined others who had slipped out earlier. But the vast majority, like Abraham David, were rounded up in “actions” and loaded on trains to concentration camps or taken to the nearby forest of Ponary and shot immediately. By the end of the war, 70,000 Jews of Vilna were shot at Ponary, either by Germans or by their Lithuanian collaborators.

The three surviving members of the Lidskyfamily, Betsy, Alexander and Tolka, were sent as labor to Heeres Kraft Park (HKP), a factory outside town. Wilhelm Begell was sent there too and he remained a lifelong friend of Alexander Lidsky. In HKP, the 13 year-old Begell kissed a girl and the 22-year old Alexander told him that because of this the girl got pregnant. Begell knew better.

At this point in the war, the Germans suffered from a severe shortage of gasoline. For this reason, at HKP, trucks were converted from gasoline power to charcoal power. Alexander and Wilhelm were assigned jobs making hinges for the new engines. The German Nazi commander of the camp, Major Plagge, was miraculously a benevolent character. Begell attested to this. In May 1944, as the Soviet Army was approaching Vilna, the Nazi SS decided to liquidate HKP prior to their retreat. Major Plagge assembled everyone outside and made the following announcement: “In a few days, my command here will end and HKP will come under the control of the SS, which, as you know, holds the welfare of the Jews as its highest priority. There is no reason for you to be afraid, because they will look after you.” Major Plagge risked his life : this extremely ironic statement was a loud and clear warning to the Jews that they were in extreme danger.

Tolka Lidsky in the courtyard of the Jewish Hospital in the Vilna Ghetto, during Nazi occupation of Vilna, 1941-1944

Betsy, Tolka and Alex hid in a maline, a hiding place behind a false wall in their building. Tolka had a girlfriend who was not in the maline with them. Outside Germans announced on megaphones that they were about to dynamite the buildings, but that those who came out would not be hurt. In a split second decision, Tolka, ran out to the staircase and was grabbed by a Nazi. He was taken to Ponary and shot. (For the remaining fifty years of his life, Alexander blamed himself for his twin brother’s death: “I should have held him and not let him go.” He engaged in self-destructive behavior, including alcohol abuse. He finally took his last drink in the 1970’s after his wife asked him to choose between her and alcohol.)

Not long after Tolka was shot, the Germans abandoned HKP and Alex walked out of the camp. It was not safe outside the camp either. Germans and their Lithuanian collaborators were still killing Jews. The Russian army had not yet liberated Vilna from the Nazis. With his shaven head, it was obvious that Alexander was a Jew who had just left a camp. He covered his head with a cap and took a ferry on the Vilya River, which runs through Vilna. A man on the boat said to Alex in perfect Polish, “be careful - they are shooting Jews on the street.” Alex replied that he was glad the man was Polish, and not Lithuanian. The man said that he was in fact Lithuanian and he gave Alex some black bread.

Alex got off the ferry and sat on a beach by the river, waiting out the departure of the Nazis and the arrival of the Soviets. He tried to act calm and nonchalant, but he knew how unsafe it was.

Alexander and his mother reunited and resolved to get to an American-occupied zone in Germany. They stayed at a Displaced Persons Camp near Munich while they waited for permission to go to America. Betsy could go first because she was an American citizen, being born in New York. She arrived in New York in 1945 and Alex joined her in 1948. Betsy Lidsky washed floors in the hospital while she studied for her American medical examinations. She later worked as a pediatrician at Yiddish summer camps north of the city. Alex washed dishes in a restaurant and worked as a shipping clerk while he attended night school at the City College of New York, studying electrical engineering. After graduation, he worked for Western Electric, which at the time manufactured most of the telephones and switching equipment in the United States. He lived with his mother in an apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

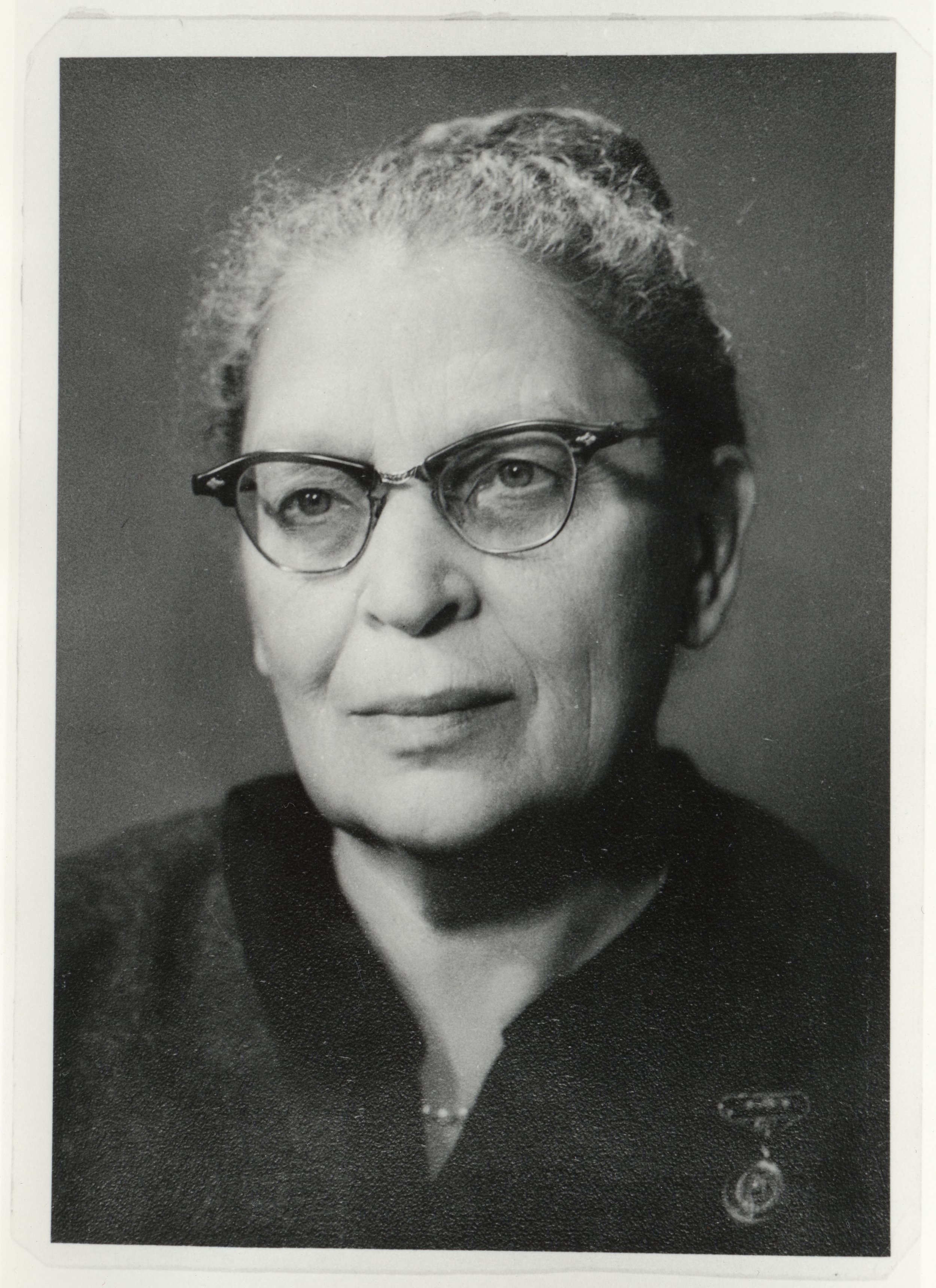

Pesia (Betsy) Lidsky (nee Weinstein)

Betsy worried about her son. He was single, drank, came home late at night. She received a phone call early in 1963 from a woman named Ella Cwik. Ella explained that she was visiting from Israel, but that she grew up in Vilna and someone had given her Betsy’s number. It turns out that Ella and Alex were not just from the same town, they were from the same street, and the same apartment building. Before she was killed, Ella’s mother owned the apartment building and the Lidskys were her tenants. When Ella’s mother had breast cancer, Dr. Abraham David Lidsky assisted with the masectomy. Betsy invited Ella for dinner. When Ella arrived, Alex was in the apartment and the two had a lot to talk about. Alex didn’t remember Ella from Vilna, because she was younger. But Ella distinctly remembered two tall twins walking on her street. On the same day that they met in Betsy’s apartment, Alex asked Ella if she would marry him. She said she didn’t know. But she went out with him every night after that. It was very refreshing for her to talk to someone who knew her parents and her sisters from before the war. It was a quick courtship. Seven weeks later they were married.

Alex had one son, David, and later moved with his wife and child to New Jersey. Betsy would often come to stay at the house in New Jersey. Betsy Lidsky died of stroke in 1979. Alex Lidsky died of cancer in 1996.

The Cwik-Izakson Family

Ella Cwik is the youngest of the eight children of Leib Cwik and Sheina Izakson. Her older siblings were born in Radoscowicz, a small shtetl outside of Vilna. Around the time Ella was born (1923), the family moved to Vilna. While Leib devoted his time to studying the holy texts, Sheina earned a living for the family. She ran a store and later became the landlord of an apartment building on Zawalne Street, where she lived. Sheina was successful in business and her family was well off. There were two boys and six girls.

Ela Cwik (later Ella Lidsky)

The first child, Fania, knew how to read and write, but was not formally educated. Fania’s mother, Sheina, wanted her to marry an educated man and offered a large dowry. The parents made a shiduch (arranged marriage) between Fania and a high school professor named Pasynski. They had a child, Leah, but the couple had nothing in common and Pasynski took a mistress. The couple divorced, but apparently Sheina had not learned her lesson. She made another shiduch, with a dentist named Belkind, paying for his dental school. Fania gave birth to a boy named David, but the husband and wife had nothing in common and Belkind took a mistress, and divorce followed. By this time, some of the other sisters were in love and wanted to marry, but Sheina made them wait. Jewish tradition dictated that the older sister had to be married first.

Ella Lidsky recalls her childhood as an idyllic time. Not only was she the youngest of eight children, but eight years passed between her birth and that of the next youngest sister. Ella was not much older than her niece and nephew, Leah and David. Since her mother was much older, her sisters played a large part in raising her. Her sisters nicknamed her, wyskrobek (the rice that is left sticking to the bottom of the pot and that needs to be scraped out). They would play with her like a doll and lovingly toss her back and forth to one another.

They spoke Yiddish at home, but her parents sent her to a Polish language high school. She had a friend named Dobka (Dobcia) Rabin.

In September 1939, Poland was divided. The Nazis occupied the western part and the Soviets occupied the eastern part, including Vilna. Ella’s parents were put in the Lukishki prison for the crime of being bourgeois property owners and traitors to the people. They were released after one week. Their apartment building was nationalized (confiscated), but they were allowed to keep the apartment in which they lived. In the early days, the Soviets were confined to garrisons and did not occupy residential areas of Vilna. On October 28, 1939, Vilna was taken over by the Lithuanians. That day was marked by anti-Jewish riots. Ella was at home and all of a sudden Dobka Rabin’s pregnant sister came running into her house, terrified. Some Lithuanian hoodlums had been chasing her. This scene made a great impact on Ella. She told her mother that she did not want to be in a place where Lithuanians chased pregnant Jewish around in the streets and cut off the beards of Jewish men. Her mother acquiesced and let her finish her final year of high school in Grodno (eastern Poland before the war, now Belarus) . She and her older sister, Mera, went travelled there by train. A guard said to Ella, “You are too young; you have to go back home. Come back when you grow up.” But then another guard said to the first, “But she is with her older sister.” They allowed the sisters to continue to Grodno. Ella stayed in Grodno, living in the high school dormitory, while her sister returned to Vilna. After, graduation from high school (desiatiletka), she enrolled at the Lviv Pedagogical Institute. Lviv is the Ukrainian name; before the dissolution of Poland, it was known as Lwow. When she came home to Vilna for winter vacation, her mother, Sheina, gave her a brand new dress and coat. Ella was quite pleased because, until this time, Ella had worn hand-me-downs from her sisters. Sheina told her daughter that if anything bad happened while she was in Lviv, she should drop her dress and her coat and come straight home, just wearing the clothes on her back. Ella did not realize it, but this would be the last time she saw her mother, father, niece, nephew, and all but one of her seven siblings.

In June 1941, Ella was in her dormitory when the Germans started bombing the USSR. She ran outside. There were dead people lying in the street. She hid under a truck until the bombing stopped. The driver took her to the train station. Remembering her mother’s advice, she asked for the train going to Vilna. The conductor told her that there were no more trains to Vilna and that she needed to get on the train to Kiev right away, because the German Army would be in Lviv in a matter of hours. So she boarded the train to Kiev, thinking that she could go back to her mother in Vilna after she got to Kiev. On the way to Kiev, the bombing started again, the train stopped and Ella got out. Chava, whose bed was next to hers in the dormitory, was on the ground, her leg injured. After the bombing stopped, Ella carried her back onto the train. Another girl on the train said to Ella and Chava: “It’s dangerous here. Let’s not go to Kiev. I’m going back to my parents in Galicia. Come with me.” The next time the train stopped, the girl did not get back onboard. Ella never saw her again.

Chana Cwik

When Ella arrived in Kiev, she went to the post office and spent her last ruble on a telegram to her parents, telling them she was safe. To this day, she does not know if they ever received it. She stayed for a week, sleeping in a high school gymnasium. The authorities divided the young people by sex: boys were sent to dig fortifications to stop the German advance: girls were sent to a kolkhoz (collective farm) outside of the city of Kremenchuk in the Ukraine. Ella and Chava were now part of a group of five girlfriends that helped each other survive. They collected wheat from 4 in the morning until dark, but they were fed and not hungry. Thirty women slept in a room. There was a large public outdoor shower. Sometimes the men would enter before the women finished bathing. Vita, two years older and wiser than the others, worried that the Germans would eventually reach their kolkhoz in Ukraine. She suggested that they go to refugee center in Kremenchuk, where the Soviets were issuing ration cards, including 600 grams of bread per day, to refugees like them. The girls knew that the kolkhoz officials would not let them leave, so they left quietly. Traveling by foot and sometimes getting a ride on a truck, they arrived in Kremenchuk and received their ration cards. The weather was starting to turn colder. Ella’s skirt was getting thin: it was made from a potato sack. Her shirt was made of medical gauze. When the Kremenchchuk officials asked where the girls wanted to go, they answered: “where it is warm.”

They travelled on a cattle train and were given bread and water at each stop. On the journey that lasted one or two weeks, they met refugees from other places. It seemed like all of Russia was moving.

They arrived at a sovkhoz in Dagestan in the Caucuses, where they harvested fruit, mostly melons and watermelons. After working there for a few weeks, Leah suggested that they leave for Maykop, where there was a teacher’s seminary. They rode on trucks when they could find them, and travelled by foot the rest of the time. Leah presented her previous report card to the school. Since she was an A student, the school officials admitted her and gave her a stipend. Ella and Masha weren’t straight A students, so they did not receive a stipend. The seminary provided the students with free housing, but no food. Part time, they worked in a factory as cleaning women and were paid cash. It was hard work and they were still hungry. Masha said to the others: “Let’s leave school and go to the director of the factory and ask for full time work.” The director was a good man. When he heard this, he said: “No way. I have a daughter your age. The reason I hired you is that I want you to be in school. If you leave school, I’ll throw you out of the factory”.

Odessa was now occupied by the Nazis and Odessa Pedagogical Institute relocated to Maykop. Ella transferred from the Maykop teacher’s seminary to Odessa Pedagogical Institute (which was now in Maykop). The institute gave food to the students, but it was a watery soup with a few crumbs. The priority was to feed the army. The girls worked after school and on weekends. They carried sacks of grain from the fields to the trains. With the cash that they earned, they bought some more food, but they were still hungry. The girls got free winter jackets from the school. In August 1942, the Germans started bombing Maykop and the University evacuated its faculty and students. Two cars of a train were allocated to Odessa University in Exile (OUIE). These cars carried portions of the art collection, library, and laboratory equipment. Also, older faculty members rode on the train. The younger professors and the students were given meeting points. They travelled from meeting point to meeting point. When available, they rode on truck or train; at other times, they went on foot. Some days, they would not travel, but would work in the fields on a sovkhoz or a kolkhoz. They embarked on a boat at Baku to cross the Caspian Sea, disembarking at Krasnovodsk (current name is Türkmenbaşy) in Turkmenistan. OUIE travelled to several capitals in several Soviet Asian Republics but most major cities were already hosting evacuated Russian Universities. They turned back to Turkmenistan and were accepted in Bayramali, roughly 5000 kilometers from Odessa. Ella graduated with her degree in Slavic Languages and Literature in the spring of 1944. In her last year, she taught part time at a local Polish language school for the children of Polish families living in Bayramali. The following year, she taught there full time.

At the end of the school year, Ella went to Moscow to attend a seminar for teachers, and she did not return to Bayramali. She was admitted to Moscow University, but they provided no housing. So she enrolled in the Stalin Institute of Metallurgy, which gave her a place in a dormitory. The problem was that Ella excelled at humanities, not metallurgy. A boy who was in love with Ella tried to help her, but it was impossible. She quit before the semester was over. A woman who worked for the Organization of Polish Patriots lived in the Hotel Moscow and treated Ella like her own daughter. She let Ella live with her and got her a job in the same organization. She worked for the organization until the Soviets allowed her to return to Poland in 1946.

Vilna was not in Poland anymore. It was now Vilnius, capital of Lithuania. Ella knew that her parents and her siblings except for Pinchas were dead. Still, she wanted to return to see Vilnius. But the Lithuanians would not allow her entry. She went to Warsaw and tried to get to Vilnius from there, but still had no luck. In Warsaw and met an army general, Jewish and much older than Ella, who lived with his sister. He wanted to marry Ella, and she said maybe. In the meantime, Ella found out that her cousin, Shlomo Cherches, and her cousin-in-law, Naphtali, were in a little town called Dzierżoniów. Shlomo’s sister and her child had been killed in the Holocaust. In Dzierżoniów, Shlomo fell in love with Ella. She liked him but did not want to marry him. Ella was bored because the two men worked during the day and she had nothing to do. After work, they taught her to smoke cigarettes and ride a bicycle. When she was a child, she had never had a bicycle. She fell off the bicycle and hurt her leg and didn’t try to ride a bicycle after that. After two weeks in Dzierżoniów, she returned to Warsaw and told the general that she wanted to marry him. But this time, he said, “No. I’ll marry you and in a year you’ll divorce me”. But they still stayed friends and he invited her to dinner. In her later years, Ella reflected that he made the right decision.

Ella left Warsaw for Wroclaw (it used to be Breslau in Germany before the war), where she took a job as a principal at a Jewish kindergarten. Her education had prepared to be a high school teacher, but she took the job anyway. She was with the children at a summer camp when an epidemic broke out. She and the children were quarantined and the parents were not allowed to take their children home. A Jewish doctor in the hospital fell in love with Ella and for this reason took extra good care of the children. She was scared that the children might die and she decided not to teach kindergarten after that. She went to teach Russian language and literature at a high school for boys. Ella was pretty and sometimes only two years older than her students, because some of the boys had lost years during the war. She always found flowers on her desk. As a teacher, she had ample vacations and she liked to go to Zakopane, in the mountains. There were dances and activities for young people there. Ella was also called Helena in Poland. At dinner several young Polish men came to her and wished her happy St. Helena’s day, since it was that saints name day. Ella told the men that she was Jewish and seemed very surprised. One of the men remained friendly with Ella and she dated him. He wanted to marry her and invited her to his aunt’s house. There, she saw a picture of the Virgin Mary on the wall and thought to herself, “What am I doing? My whole family was killed for being Jewish and now I’m becoming Catholic.” She stopped dating him. At a New Year’s Eve party at the Wroclaw Jewish Community center, she met a boy, a journalism student. There were not enough chairs. They shared a chair, talked and kissed. He lived in another town, Katowice. After that, they corresponded by mail. He would write beautiful letters. He wrote that they were too young to get married. Once, Ella came to visit him in Katowice. Then Ella contracted tuberculosis and was barred from teaching. She spent a whole year at a sanatorium in Zakopane. No medicine, just good food and fresh air, led to her recuperation. She met a Catholic girl who wanted her to convert to Catholicism, saying she was ready to die for her. Ella said the she was Jewish and that she wanted to stay Jewish, but they still remained friends.

Because of the tuberculosis, Ella was barred from teaching, a profession that she loved. She left Wroclaw for Warsaw took a state job in an office of international trade, called Cekop. She did Polish-Russian translations. Occasionally, she freelanced and made much more money: in one Sunday she could earn a month’s office salary. At work one day, Ella learned that the boy she had been corresponding with, the journalist, had married another journalist. She went to the bathroom, sat on the toilet, and cried. She had been in love with that boy.

Ella had one surviving sibling: her brother Pinchas. At the age of 23, Pinchas was caught smuggling goods across the Polish-Russian border, arrested, and put in a Soviet labor camp, digging mines. After seven years, Pinchas bribed a guard with his fur coat and escaped. Pinchas was quite short, not much more than five feet, but very strong. He managed to travel a long distance back to his home in Vilna. Sheina bribed Polish officials so that they would not send him back to Russia. They agreed not to turn him in under the condition that he leave the country immediately (they didn’t want trouble with the Russians). He stayed home for a week or two and then left for Palestine, thus avoiding the Holocaust. He didn’t know it at the time, but getting arrested for smuggling most likely saved his life.

Top: Pinchas Cwik, Bottom: (left) a friend, (right) Chana Cwik

Ella had been corresponding with her brother since shortly after the war. There was a Jewish woman in Mari, not far from Bayramali, who had two sons in Palestine. The woman wrote to her sons that her friend had a brother living in Magdil, a small town in present day Israel. Shortly after that, Ella received a letter from her brother, asking him to join him, but in 1946, she was not a Zionist and did not want to leave for Palestine. By the 1950’s she had changed her mind, but she had difficulty getting an exit visa. In 1957, after working for Cekop for seven years, she was granted a one-way exit visa. She took a train to a port in Italy and from there boarded a ship to Haifa, Israel. She was not allowed to take currency out of Poland, so she bought a refrigerator took it with her on the ship! Before the ship landed, representatives from the state of Israel came on board and interviewed the passengers. They told here, “You were a teacher in Poland and you’ll become a teacher on a kibbutz”. Pinchas met her at the port of Haifa and carried the refrigerator on his back as if it were nothing. But Pinchas did not need a refrigerator; he already had one. He also told her not to go to the kibbutz, but rather to come stay with him. She stayed with her brother for two weeks, communicating in Russian. She also met Pinchas’s daughter, Nira, who was 20 years old, beautiful, and a singer/actress on a children’s show called sumsum. But Ella could not communicate very well with her because she spoke no Hebrew.

In Magdil, Ella fell down and broke her leg. It was hot, and to make matters worse, she could not take a shower because she was in a cast with a broken leg. Ella’s cousin Chaim Nachshon took her to his house in Afeqa and cared for her, even carrying her to the toilet each time she needed to use it.

She enrolled in an ulpan (Hebrew language course for newcomers) for half a year Her cousin Chaim HaAfter that, she worked as a cashier at a supermarket in Tel Aviv. Not being strong in math, and not having mastered the new language, it was difficult for her to count money and make change. She wrote to her friend Edward Zawada that she regretted leaving Poland. Edward was no the Minister of Chemistry for the Polish government. He said that it would be difficult to arrange for a return to Poland, given her one-way exit visa, but that he would try to help her. Ella said no. Maybe she was wrong to leave Poland in the first place, but if she returned now, what would the people say? That a Jewish woman left Poland for Israel because she did not want to stay in Poland, but now she is not happy in Israel and wants to come back to Poland and get a job there? Ella also confided in a friend that she had met on the boat. Her friend told her, “This is not a job for you. Why don’t you enroll in the Teacher’s Seminary in Beersheba?” Ella called the seminary; she would receive free tuition, but no money for food. Her brother Pinchas sent her money for food and expenses.

In Beersheba, she studied the history of the Jewish people, the history of Israel and how to be a teacher. After graduation, she got a job teaching second grade in Ber Yaakov, not far from Tel Aviv. The children loved her. They would meet her at the bus: one would take her hand and the other would take her bag. Their first grade teacher was a sabra (born Israeli), but she had not had the time to teach them well because she was preparing for her exams for the university in Jerusalem. At the beginning of second grade, the children still did not know how to read, write or count. Ella worked with them during school and after school to help them catch up. She also sang for them and celebrated holidays with them. When they looked into her eyes, she thought about her sister’s children, Leah and David. If there had been an Israel earlier, there would have been a place for Leah and David to go. Nobody wanted the Jews. Ella was finally a Zionist. An unmarried Zionist.

A man from London came to Israel to visit his sister. He met Ella, spoke about marriage, and said he needed to go back to London, but that he would return. In the meantime, somebody introduced Ella to a rich man from Los Angeles, also visiting his sister. This man fell in love with Ella. Ella’s cousin Naphtali said, “Why don’t you marry him. Then you can send us money from the United States?” Ella accepted the Los Angeles man’s proposal and invitations were sent out. But then she thought to herself, “What am I doing? We have nothing in common.” She backed out of the marriage on the day before the wedding date. Naphtali supported her. He said, “Don’t worry. People will talk. But call it off – otherwise you’ll be unhappy all your life.” The Los Angeles man understood and forgave her, but Ella thought his sister would kill her. In the meantime, the London man, whom Ella really did like, returned to Israel. But someone told him Ella was already married and he went back home without seeing her.

In 1960, Eli and Ida Lapidus, Ella’s cousins who lived in Paris, came to Israel and invited Ella to stay with them in France. Ella said no. She had mastered Hebrew well enough to read the newspaper and listen to the radio. She did not want to go through another round of immigration. But she said she would like to come visit them in the summer of 1961.

One day in 1961, at the end of the school year in Ber Yaakov, she came home and found a note from her American cousins, Philip and Leah Hochstein, inviting her to breakfast at their hotel in Tel Aviv. On the way to Israel, they had stopped in Paris and met with Eli and Ida, who told them where to find Ella. At breakfast, Philip and Leah invited Ella to come to the United States and be part of the family. She repeated to them what she had already said to Eli and Ida: “I already know Hebrew well enough to be a second grade teacher. I already went through one round of immigration. I don’t want another one.” Besides, she was supposed to go to Paris that summer. The Hochsteins left, but then Ella received a letter with a round-trip ticket to New York, for the July 1st wedding of Philip’s youngest daughter, Debbie. The school year ended on July 1, so Ella arranged for a substitute teacher for three days and left on June 28th. The Hochsteins picked her up at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York City. They treated her very well and asked her to stay permanently. Ella said no, but she agreed to stay for a few months. She enrolled in school to learn English. Someone told Ella that Dr. Betsy Lidsky was living in Manhattan. The Lidsky family and the Cwik family had lived in the same apartment building in Vilna. Ella called Betsy and got invited to dinner. Betsy’s son Alexander was there. He did not remember Ella, but he remembered her parents and her older siblings.

They were married on February 20, 1963. Alexander gave Ella two “conditions”: 1) he did not want to bring children into the world because of what he saw the Nazis do to children, and 2) they had to live with his mother because they had survived the war together. Neither of these “conditions” were kept for long. The three lived in the same apartment: husband, wife, mother-in-law. An advisor for new immigrants suggested that, with all the languages she knew, Ella get a Master’s degree in library science. He gave her a 300$ loan because Alex was constantly losing his money on the stock market. Alex’s mother, Dr. Betsy Lidsky, was a pediatrician. She had taken care of children her whole life and she wanted her own grandchild. Alex’s friends also talked to him about having children and he changed his mind about one of the “conditions”. On December 23, 1964, David Abraham Lidsky was born while Ella was a Master’s student at Columbia. His father and his father’s mother wanted to name him after Abraham David Lidsky, but Ella like the name David better, so they reversed the order of the names. After maternity leave, she worked as a librarian for Columbia University Teacher’s College. While working, she entered a Ph.D. program in education. She became worried about her son after one of the librarians she knew was robbed. Ella convinced Alex to buy a house in nearby Teaneck, New Jersey. More grass is less mother-in-law. It was difficult for Ella to continue her work and her Ph.D. studies at Columbia while commuting from New Jersey and taking care of her 3½ year old son. She stopped at a Master’s degree in education and stopped working as a librarian for Columbia. She took a job as a librarian at Fairleigh Dickinson University (FDU) in Teaneck, where she could walk to work (she did not know how to drive). She hired a sleep-in babysitter for her son, but the babysitter would call her at work and say, “Your son is crying.” Her husband, Alex, said “What is more important: your son or your job?” Ella broke her FDU contract and stayed home with David. When David turned 6, she accepted an offer from a new school, Ramapo College. She set up the library and worked there for two years. After that, she worked as the Assistant Librarian at FDU, Madison campus, for 13 years. Her brother Pinchas died naturally in Israel in 1979. From 1985 until 2000, she worked as a law librarian in the U.S. Court of International Trade in New York. Her husband Alex died of cancer in 1996.